Abandoning the Mahatma, engaging with Gandhi

Faced with a rising tide of Hindu majoritarianism, it is worth engaging with Gandhi in 2021 — but with the freedom to see what might help us, and to discard what might hold us back.

There are few people whose ideas have been as effectively buried in their legacy as Mohandas K Gandhi. Sooner or later, most popular debate on Gandhi tends to devolve into a “he was a saint”/”he was a bully” contest. Reams of newsprint are devoted to anecdotal renditions of the known and lesser known aspects of his life, and prominent Gandhi scholars seem focussed on keeping the debate there.

It is hard to escape Gandhi in India. His face is on every currency note, a Mahatma Gandhi Road exists in almost every town and his face smiles benignly at visitors to every government office. Any protest in independent India is immediately given or denied legitimacy based on whether it is “Gandhian” or not and it’s a rare for a decade to go by without a popular work on Gandhi. And yet, this carefully crafted monolithic legend of the Mahatma has not served his ideas well.

First, this deification has allowed his pronouncements to be used, where convenient, while entirely ignoring the methods he recommended in relation to such goals. Recent regulation against cow slaughter is a good example of this. Gandhi’s unequivocal view that the end of cow slaughter must be brought about by convincing other communities to give it up voluntarily, and never by imposition or force, is entirely ignored.

Second, it has been used to exclude from our history the stories and arguments of several groups that did not agree with him in his lifetime and has delegitimised or discredited any attempt by such groups to voice their doubts of his views since his death. This has made critical engagement next to impossible, with many groups turning to the next best alternative — rejecting all of his ideas outright.

To clear the path for us to engage with Gandhian ideas — and I believe that is an exercise which holds value as we face a rising tide of Hindu majoritarianism — we need to start afresh. And to do that, it’s important to spend some time dismantling the Mahatma myth and acknowledging the harm caused by its propagation.

Dismantling the Mahatma myth

I’m just going to come out and say it — Gandhi often isn’t particularly likeable. His endless pronouncements on pretty much everything are often sanctimonious and his extreme individualism is sometimes hard to distinguish from garden variety selfishness. His fast around the Poona Pact, his troubling “experiments” with celibacy and his deviations from rationality, whenever convenient, memorably his “earthquake as a punishment for practicing untouchability” explanation that so shocked Rabindranath Tagore, all paint a picture that is, to put it bluntly, unflattering .

Deeply rooted in both pragmatism and individualism, Gandhian ideas also often turn status-quoist in effect. His social reforms were undeniably slow, as they relied on changing individual minds and not on challenging institutions that propagated regressive views. This is evident in his championing of the villages and the panchayat system. While it is true that existing structures and institutions can be extremely powerful tools of action — the recent mass overnight mobilisation of farmers by khap panchayats to rush to aid of farmers threatened at the Delhi border is a good example of this power — these institutions can and often do use the same power to maintain regressive social structures, including through the violent enforcement of existing religious, caste and gender hierarchies. On caste, this is a particularly bitter legacy. His attempts to redefine and preserve a form of the caste system (while challenging untouchability) have been seen by many to have served the interests of caste Hindus far more than the community he ostensibly sought to champion.

While there is much to debate here, the Mahatma tag has often been used to stifle all such debate. In the realm of popular discussion, “Gandhi said…” is treated as the end of all argument, instead of the starting point of the discussion. This has not been helpful. Without a broader acknowledgement of Gandhi’s flaws, or license to dislike Gandhi if you will, the Mahatma myth makes any meaningful engagement with his ideas impossible. One is forced to either agree completely (usually impossible) or to dismiss all his ideas outright. Neither approach serves us particularly well.

Reexamining Gandhi today

In Hind Swaraj (1909), Gandhi articulated a broad sweep of his ideas - on medicine, on education and on civilisation itself, but we can leave most of them aside and focus on his idea of Swaraj or self rule. For him, it was a concept broader than the transfer of political power from British to Indian hands. He argued that political independence would be meaningless if it didn’t include Hindu-Muslim unity, the eradication of untouchability, and the propagation of spinning (as a form of non-agricultural rural employment). In 2021, looking at an almost overwhelming swing towards “might is right” in all forms of governance, political dominance through terrifying communal polarisation, and a serious agrarian crisis, it’s clear that 74 years after independence, this concern remains valid.

In this context, it is interesting to reexamine Gandhi’s work on communal harmony, and more particularly, his on- ground work in 1947.

Combating riots

In Hind Swaraj, Gandhi articulates his idea of a pluralistic India. He says:

“If the Hindus believe that India should be peopled only by Hindus, they are living in dreamland. Hindus, Mohammedans, Parsees and Christians who have made India their country are fellow countrymen and they will have to live in unity if only for their own interests. In no part of the world are one nationality and one religion synonymous terms nor has it ever been in India.”

But as always, Gandhi’s methods are of more interest. Perhaps there is no more fascinating year of Gandhi’s life than 1947. Generally made redundant by the Congress, he returned to where he felt that he would be most useful — the riot affected areas of Noakhali (now in Bangladesh) and Bihar— to “do or die”. Viewed in the context of his assassination at the hands of a Hindu extremist less than a year later, this was no idle promise.

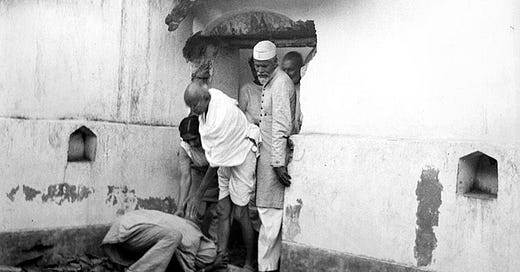

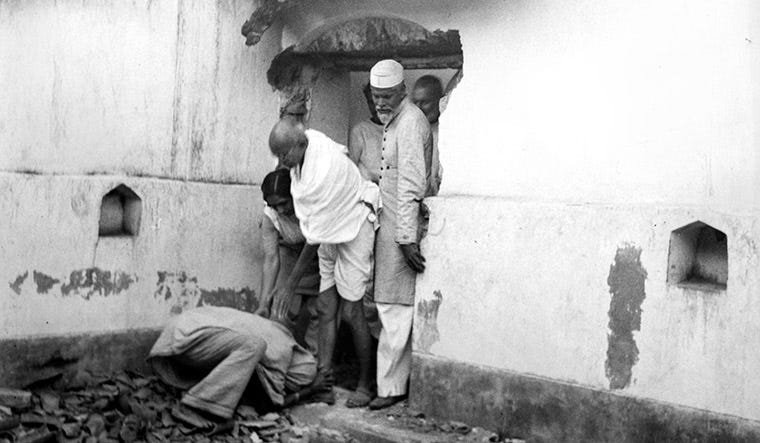

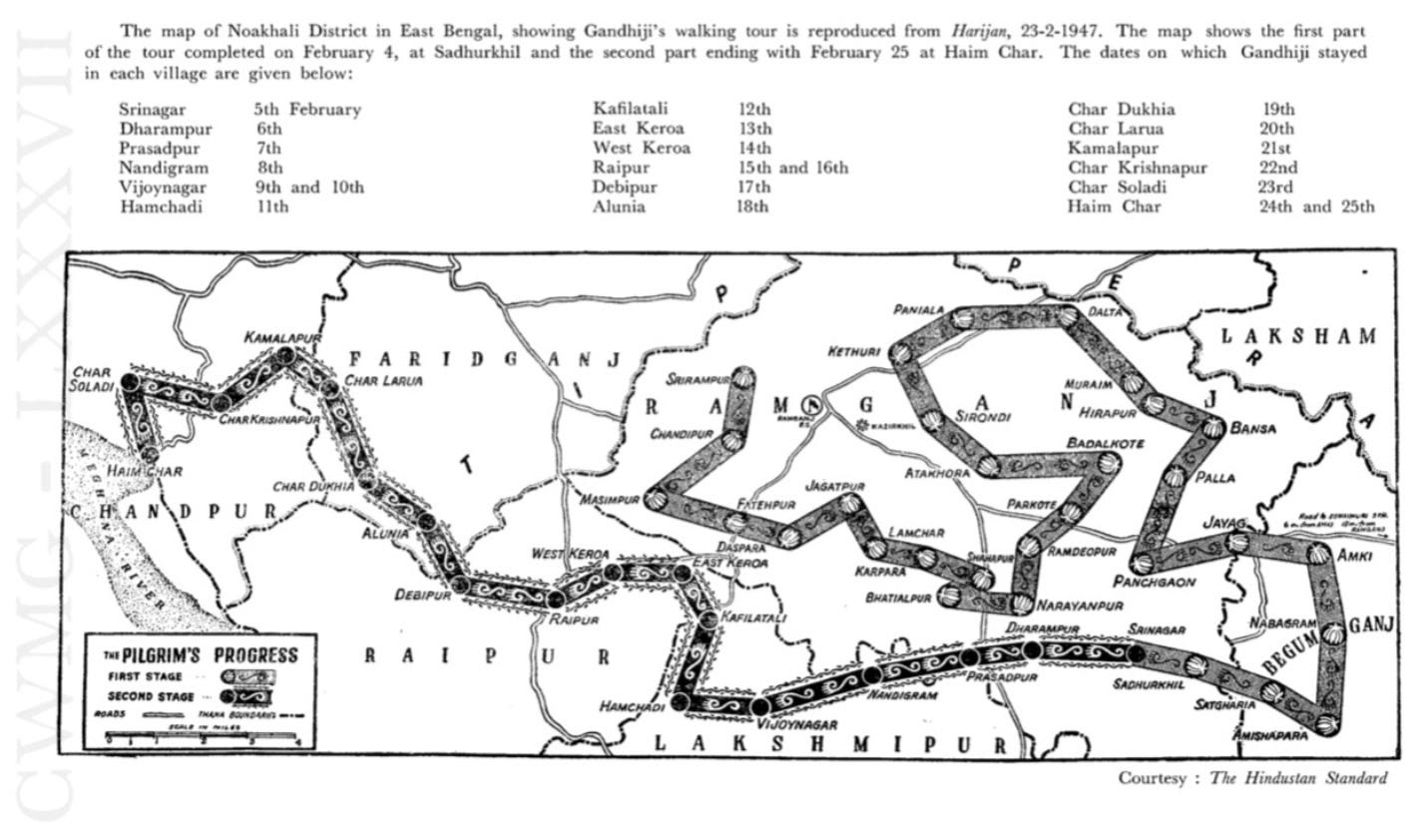

Thanks to the prominence of the Mahatma myth, there is a popular belief that Gandhi just showed up in riot prone areas, fasted and peace immediately prevailed. This is not quite correct and doesn’t do justice to the vast amounts of time and effort he spent in riot affected areas in 1947, often making little or no progress. Gandhi began the year in Noakhali, where Hindus had been driven out of their homes in riots since October 1946. His work involved a walking tour of riot affected areas, meeting victims, perpetrators, other villagers, Muslim League members, and liaising with the local League government (including HS Suhrawardy, who famously called him “an old fraud”) to negotiate safe passage back to their villages for riot affected Hindus.

He stayed in Noakhali until the beginning of March, when the summons for help from Bihar, could no longer be ignored. Dr Syed Mahmud of the Congress had written to Gandhi (without consulting the rest of the Congress ministry in Bihar), in response to his enquiries detailing what was happening. Arriving in Bihar in early March, with the intention of staying for no more than two weeks, Gandhi realised with growing horror that the reports he had heard of violence against Muslims in Bihar, that he had put down to the exaggeration of the Muslim League, were far from exaggerated. In Bihar, his methods were similar to the procedures he followed in Noakhali. Walking tours, visiting villages, meetings with both victims and perpetrators, meetings on the logistics of resettlement with the Congress government and Muslim League volunteers and prayer meetings. But in Bihar (where he wielded greater influence with the majority community than in Noakhali), he made a concentrated effort to encourage people to take responsibility for what had happened — both individual and collective. In a prayer meeting in Patna on March 5, 1947, he speaks of the “great sin”:

When I came here, and saw the conditions here, I realised that we had indeed committed a great sin here. It is our duty to atone for our sin and do reparations.

The words he uses are interesting — “we”, “our duty” — he doesn’t try to limit responsibility to the perpetrators, or even the authorities who stood by and let the violence happen (though he does strongly reprimand them in smaller meetings). He is very clear that it was the majority community’s responsibility to protect their entire village, and that their failure to do that was their “sin”. He often met with perpetrators and encouraged them to turn themselves in to the authorities (a few did), but at the centre of his work was bringing entire villages to acknowledge responsibility and make reparations. Often he asked them to clean and rebuild the destroyed homes, pay the expenses involved and invite their former neighbours back. He also collected funds for the resettlement of the displaced in each village that he visited and at each prayer meeting he held. These methods were not always effective as the trauma of the violence was at times too great for families to return, but they serve to highlight a larger point that is entirely absent from our liberal discourse on communal violence today — taking responsibility.

Most liberal (and usually upper caste) Hindus today shy away from taking responsibility for what has happened to the country. We speak of the Constitution and secularism and the failure of institutions, but we shy away from the core question - how did we let our community become this radicalised? We blame the courts, the police and the government, but we stop short of examining ourselves and the role played by our immediate communities in the rise of Hindu majoritarianism. Gandhi wouldn’t have let us do that. What has happened today is, to use his words “our sin” and therefore also our problem to rebuild what has been destroyed, and to protect minorities from further harm.

Conclusion

While much is written about non-violence, there are other learnings from Gandhian method, in confronting an authoritarian state. A large part of Gandhi’s work demonstrates that any state, no matter how authoritarian, can be made redundant, if local communities choose to do so. There is also a message of some hope: What has been destroyed can be rebuilt, but this will require the hard work of taking responsibility for what has happened, engaging with our own immediate communities, changing minds and building trust. It will require us to do more than tackle the political, judicial or institutional crisis we face. It will require us to take responsibility for and tackle the larger social crises we are facing.

It’s certainly worth engaging with Gandhi in 2021 — but with the freedom to see what might help us, and to discard what might hold us back.