Gandhi, Jinnah and the Indian Muslim community

Inclusion, loss of trust, and finally, affection

In M.A. Jinnah’s famous 1940 Presidential Address at Lahore, while discussing the Congress proposal for the formation of a Constituent Assembly, he quotes Gandhi, who on March 20, 1940 is reported to have said,

There was a time when I could say that there was no Muslim whose confidence I did not enjoy. It is my misfortune that it is not so today.

Jinnah, in his typical acerbic style demands of the audience,

Why has he lost the confidence of the Muslim today? May I ask, ladies and gentlemen?…He is fighting the British. But may I point out to Mr. Gandhi and and Congress that they are fighting for a Constituent Assembly which the Muslims say they cannot accept.

Jinnah also remarks,

For it will be remembered that up to the time of the declaration of war, the Viceroy never thought of me but of Gandhi and Gandhi alone…I believe that was the worst shock that the Congress High Command received, because it challenged their sole authority to speak on behalf of India.

While the whole speech is of enduring interest to partition scholars, these nuggets are fascinating, because it demonstrates at the height of the acrimony between Jinnah and Gandhi, Jinnah doesn’t quite refute Gandhi’s claim that there was a time when Gandhi did enjoy the confidence of the Muslim community, and when he could legitimately claim to speak for their interests. He merely points out what Gandhi himself knew in 1940- that this was no longer the case.

The efficacy of Gandhi’s movements can be traced back to their generally inclusive nature. They were umbrella movements with a wide range of participants across faith lines, and including some hitherto excluded groups like women and Dalits. Participation, not exclusion was the focus. This was possible, in part, because Gandhi located himself in the larger arena of social reform. But as Gandhi was to find out himself, there is a fine line between inclusion and appropriation. While Gandhi did much to bring hitherto ignored causes to the mainstream, this was often at the cost of “speaking for” the community in question, which could sometimes provoke lasting resentment.

Arundhati Roy’s 2014 introduction to the Annihilation of Caste, “The Doctor and the Saint”, though rather inadequate as an introduction to that great work, does a fair job of highlighting several of Gandhi’s personal shortcomings in this regard with respect to the Dalit community, especially in the run up to the 1932 Poona Pact (though it does significantly underplay Dr. Ambedkar’s acheivements in successfully negotiating for the inclusion of reservations in parliament and public service, something Gandhi had strong initial objections to).

While Gandhi’s relationship with the Indian Muslim community did not suffer from the same sort of power imbalance that was inherent in Gandhi’s relationship with and advocacy on behalf of the Dalit community, their comfort with Gandhi and his assuming the mantle of leadership over their causes constantly changed, based on the larger circumstances.

South Africa

The South African satyagraha is broadly acknowledged to have been Gandhi’s first experience of leading a multi-faith community against the policies of a colonial government. It also provided his first opportunity to interact with M.A. Jinnah. In 1908, Jinnah was appointed by Anjuman Islam of Bombay to “proceed to England and there to place the position of the Traansvaal Indians before the people of England.” There was even talk of Jinnah coming to South Africa to aid the process.

Keep in mind that while the South African Indian community generally presented a united front against the policies of the government, Hindu and Muslim interests were occasionally divergent. In a letter published in Indian Opinion, on February 22, 1908, Gandhi speaks of the mistrust with which a few Muslim members of the Traansval Indian community viewed him, even at the height of the passive resistance movement. He writes, in Indian Opinion, in 1908 of Haji Ojeer Ally,

When the passive resistance movement was at its height, Mr. Ally could not continue to trust me fully, because I was a Hindu.

This was perhaps an oversimplification. Ally’s concerns were slightly different. In a letter to Ameer Ali, Ally expressed the view that continued resistance to the Asiatic Registration Act would harm the Muslim community, who were predominantly traders, far more than the Hindu community, who were mostly hawkers, and sought intervention against the satyagraha. Gandhi acknowledges however that he was granted the full support of the community, regardless of such objections.

Further, certain Muslim traders, unhappy with the position Gandhi had negotiated on registration actually wired Jinnah to intervene. Gandhi, speaking in 1908, notes,

Mr. Jinnah, Bar-at-Law, showed me a telegram from Mr. Mahomed Shah of President Street which says that about 700 muslims are displeased with the compromise and that they are determined not to apply for registration. I have suggested to Mr. Jinnah to say in reply that he was happy to learn from the cables that all the people were united.

While Jinnah allowed himself to be guided by Gandhi on this occasion, the whole controversy around Gandhi’s initial compromise on the Asiatic Registration Act is interesting. It is an early demonstration of a pattern that was to repeat itself later in India - while Gandhi was able to forge broadbased coalitions of communities that were able to work together successfully against the British, any divergence of opinion on the path to follow were immediately assumed to be down to religious differences and expressed as doubt in Gandhi’s ability to speak sufficiently for all interests. While Gandhi was frequently able to successfully include diverse communities in his movements, he never could quite dispel this underlying doubt.

Khilafat Movement and Non-Cooperation

Returning to India from South Africa in time for the First World War, Gandhi (unlike other Congress leaders at this time) chose not to oppose the war efforts. He instead used this time to connect with local peasant concerns in a manner that was then unique. His interactions led him to Champaran in Bihar, where he managed to successfully take on the powerful indigo interests in the area, and consequently the British government. He followed this up with work in Kheda in Gujarat, where he successfully led a protest by agriculturists against high taxes. The end of the war and the passing of the Rowlatt Act restored Gandhi to the national stage. The Punjab atrocities at the protests to the Rowlatt Act of 1919 turned Gandhi to active resistance against the British government. The Congress launched the Non-Cooperation Movement, a nationwide non-violent protest against the Montague- Chelmsford reforms. At this point Gandhi chose to co-opt the Khilafat movement into this struggle.

The brutal treatment of the Turkish Sultan at the hands of the British after military occupation in the First World War had already sparked huge resentment within the Indian Muslim community, particularly in its more religious factions. Gandhi’s alliance with Shaukat and Muhhamad Ali, and Maulana Azad and the inclusion of the religious Khilafat movement within the folds of the secular Non-Cooperation Movement was an intriguing stroke that at once gave him access to and the confidence of the Indian Muslim community that more secular leaders (ironically, at the time, Jinnah) hadn’t managed to gain, and presented a dazzling, if brief vision of a united “Indianness” that could trump the religious identities of the time.

It also provided an insight into the possibility of forging multi-faith alliances by promoting religion instead of the strict tennets of western secularism. Writing on October 26, 1919, Gandhi notes:

Swadeshi is Satyagraha. It is beyond the power of cowardly spirits to observe or to propagate Swadeshi. It is impossible for a coward to foster Hindu-Moslem unity. It takes anyone but a cowardly Mussalman to receive a wound from a Hindu’s dagger and vice-versa and to preserve his mental balance. If both could muster this much forbearance, Swarajya would be instantaneously obtained.There is none to forbid us the path of satyagraha. Both Swadeshi and Hindu-Moslem unity being in their essence religious, India would incidentally perform an act of religion.

While the Non-Cooperation Movement and the Khilafat Movement both fizzled out (the latter when the Turks themselves abolished the Khilafat and the former with the survival of the Government of India Act of 1919), this cemented Gandhi’s role, for a time, as a spokesperson for all Indian interests.

Gandhi quits the Congress

By the end of 1934 however, the civil disobedience movement was called off, and Gandhi’s more holistic approach to Swaraj (including Hindu-Muslim unity, village based economic development and the eradication of untouchability) was losing steam within the Congress. After the on-paper gains made by his fast of 1932 (entry into prominent temples and a Congress resolution abolishing untouchability), his work on eradicating untouchability through the education of caste-Hindus had hit a stone wall. After the poor performance of Dalit candidates in the municipal elections of 1933, he started Harijan in 1934 to educate caste- Hindus on the evils of untouchability. The message was unpopular, and in June 1934, a bomb was hurled at a car in the mistaken belief that he was in it.

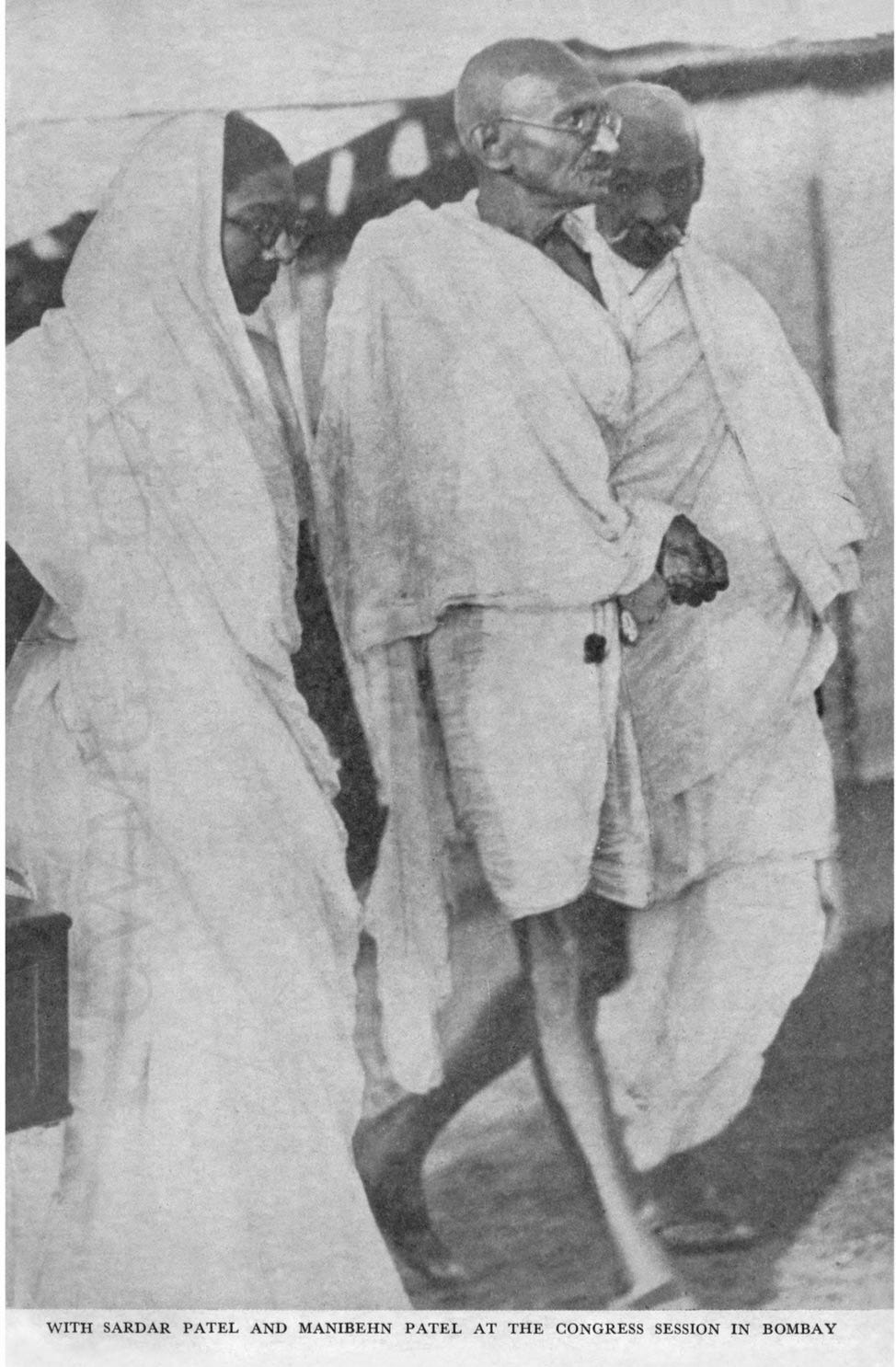

Displeased with the direction of the Congress and acknowledging his own inability to change the party anymore, and also aware of his own unpopularity with its younger members, Gandhi chose the “path of surrender” and officially left the Congress at the Bombay Congress in December 1934, and chose to focus his attention on the newly formed Village Industries Association.

The Government of India Act, 1935, separated Burma from India and provided for the creation of provincial governments in the 11 provinces left in India, with significant autonomy. While the Congress did well in the 1937 provincial elections (mostly due to its longstanding stature as an organised national party), their governance failed to win the confidence of the local Muslim communities they served. Mushirul Hassan argues convincingly that while these grievances might have been overstated, they existed, and were exceedingly difficult to dissipate. After two and a half years of Congress rule most Indian Muslims were convinced of the oppression of Muslim minorities in Congress ruled provinces. Gandhi’s relative silence in this period, and his near abdication from national politics left a void that left the party open to allegations of being controlled by the Hindu Mahasabha.

This shook the faith of many Indian Muslims in the Congress, and, incidentally, in Gandhi, whose present concerns with untouchability and the development of village industries seemed very far from their own. The united front manufactured by Gandhi in the 1920s lay all but forgotten, and Gandhi, at least in the public perception, a spent force, equally unpopular with the Congress socialists, the Hindu Mahasabha and the Muslim community.

Jinnah’s political reinvention

The Congress Muslims of Gandhi’s generation, like Maulana Azad, who clung doggedly to the message of national unity were too old to fill this void, and were opposed by both Nehru and Patel. Jinnah’s dazzling political reinvention (in the brief period between the Muslim League’s disastrous showing in the 1937 provincial elections and his fiery Lahore address of 1940) as the Qaid-e-Azam, and his open declaration that Gandhi’s vision of India was that of a Hindu raj (a declaration that must have been quite surprising to the Hindu Mahasabha) largely put paid to the idea of Gandhi as a leader that could represent all Indian interests.

In the end, affection

Gandhi’s role within the Congress in the 1940s is intriguing. He was not entirely without influence. The resignation of Subhash Chandra Bose as President of the Congress after his election in 1939 is often laid at the door of Gandhi’s interference on behalf of his chosen candidate, but in terms of any real influence on policy his role was minimal. Nehru, deeply influenced by the five year plans of the Soviet Union, and Sardar Patel, with his intense nationalist focus were both dismissive of Gandhi’s efforts to revive village economies. The RSS openly revolted against his adoption of passages from the Quran in his prayers, and even mocked his fasts to end communal violence in Calcutta in 1947. The rejection by Nehru of Gandhi’s proposed “cabinet solution” to the partition issue, further confirmed his isolation from the decisions being made by the Congress.

Gandhi accepted this sidelining. He still believed that there was room for his politics where it had all started. In the villages, away from the organised structures of the Congress. And with common Indians of all faiths.

1947, which was to be the last year of his life, was spent almost constantly in riot affected areas of Noakhali (now in Bangladesh), Bihar, Calcutta and Delhi. Even though he no longer purported to represent the Muslim community, and acknowledged their rejection of his leadership, he was still fairly warmly received by villagers in Muslim majority Noakhali. Some even contributed to the relief funds he set up for displaced Hindus. Even openly critical muslim leaders like HS Suhrawardy, the Chief Minister of Bengal (who called him “an old fraud”), didn't entirely ignore or disregard his requests. In Bihar, he was beseeched by multiple groups of Muslim refugees not to leave the area, as his presence was seen as almost the only guarantee of their safety.

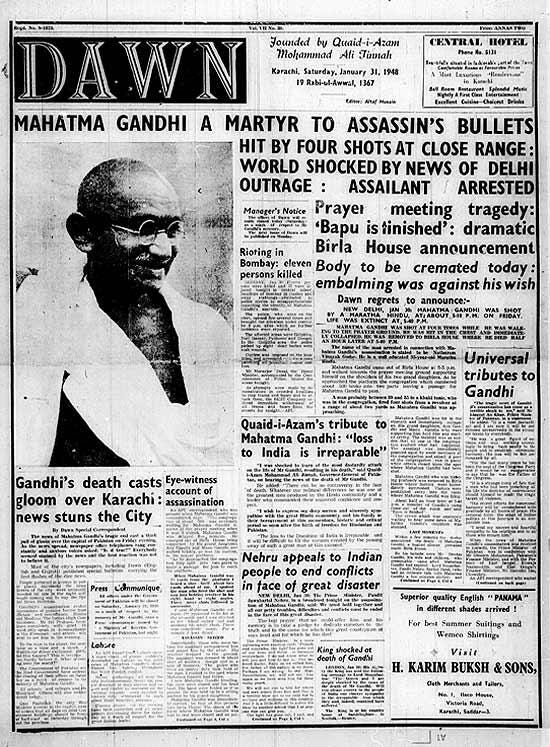

Gandhi famously spent August 15, 1947, in Calcutta, in fasting and prayer to bring peace and communal harmony. Intriguingly for such a spent political force, Gandhi could still summon leaders of both the Congress and the Muslim League to his side. HS Suhrawardy met Gandhi and publicly took responsibility for the 1946 killing of 4000 Hindus in Calcutta. Horace Alexander, who accompanied Gandhi in 1947 recounted that day as a “miracle”, without violence. And when violence later erupted in Calcutta, Gandhi began a fast which lasted from September 1, 1947 to September 4, 1947. With national leaders including Nehru and Patel rushing to his side, the riots, instigated by members of the Sangh failed to win popular Hindu support, and died down. In January 1948, he undertook a similar fast for harmony Delhi and planned to undertake further fasts in Pakistan, before which he was assassinated by a member of the Hindu nationalist Sangh.

Gandhi’s death was mourned in Pakistan. The Pakistani parliament met on February 4, 1948, and Liquat Ali Khan rose to say,

It is with a deep sense of sorrow that I rise to make a reference to the tragic death of Gandhiji. He was one of the greatest men of our times, and during the last 20 years, he occupied a great and prominent place on the stage of Indian politics. It would be no great exaggeration to say that the present strength and greatness which the Congress party enjoys is due solely to the unifying efforts of this great leader… We hope and pray that what Gandhi could not achieve in his life, might be fulfilled after his death viz establishment of peace and harmony between the various communities inhabiting this subcontinent. Mr. President sir, I will request you to send the sympathies of this house to peoples of India and Gandhi’s relations.

The Dawn, Front Page, February 1, 1948

Khwaja Nazimuddin, the Premier of East Pakistan, where Gandhi had spent so much of 1947 went further. He remarked,

I feel that his death is simply not a loss to India: it is a loss to Pakistan too. He was trying to bring good relations between India and Pakistan.

But for Indian Muslims, the loss went deeper. It was the loss of a deeply religious Hindu leader, with the stature and moral authority to reinvent the Hindu religion as an inclusive one. A leader who could retain his religious identity and mass appeal and yet advocate successfully for an India defined by religious plurality, tolerance and inclusion. Maulana Azad, speaking at the Constitution Club in New Delhi in 1948, touched briefly on this. He spoke of Gandhi’s ability to reinterpret Hinduism to a more inclusive place and of how his being a Hindu and a believer did not come in the way of embracing and respecting people following other faiths.

It is a void that is still felt in Indian politics today.