Jamnalal Bajaj, Gandhi and philanthropic capitalism

Part one of a two part series on Jamnalal Bajaj, Gandhi and the possibilities and limitations of philanthropic capitalism.

I became interested in Jamnalal Bajaj tangentially while reading about two unrelated events. The first was the Neemuchana massacre. In May 1924, a group of peasants protesting a severe tax increase in Neemuchana, in the princely state of Alwar, were gunned down and their huts and livestock were set on fire. Independent sources estimated that 95 people died and over 250 huts were burnt. In a manner frighteningly similar to the Amritsar massacre, it was suspected that a mounted machine gun was used on the protestors. A concerned Bajaj moved a resolution in the Congress Working Committee to initiate an independent inquiry into the the affair. The proposal was rejected by Mahatma Gandhi, who was wary of the Congress interfering in the Indian states. While Gandhi’s practical political position on refusing to antagonise the princely states, whom he wished to distinguish from the British, wasn’t too surprising, Bajaj’s natural solidarity for an issue affecting peasants with whom he had absolutely no ties of caste, class or geography was, to me, surprising.

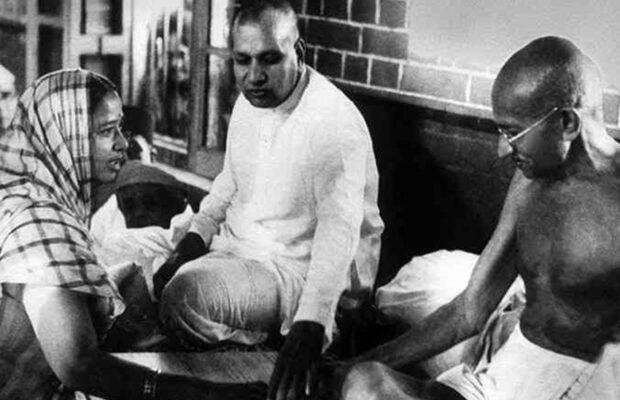

The second was in 1928, when he opened his family temple in Wardha to Dalits and also ate food prepared by a Dalit cook. This was unprecedented at the time, and for this, he was served with a notice of excommunication by his caste. This was a serious affair. For a Marwari businessman such as Bajaj, this would have meant the end of his business, and the social isolation of his family. A caste panchayat finally decided not to excommunicate him, largely thanks to an intervention by Gandhi, who wrote the defence statement himself, but Bajaj’s willingness to push the beyond the safe sort of activism many others around Gandhi limited themselves to, made him stand out from Gandhi’s many other capitalist friends.

When Bajaj died in 1942, Gandhi wrote:

Whenever I wrote of wealthy men becoming trustees of their wealth for the common good I always had this merchant prince principally in mind.

Now this is often dismissed as a statement of condolence uttered after Bajaj’s death, but it deserves deeper consideration also as a simple statement of fact. Much of Gandhi’s thinking on the possibilities of capitalists acting as trustees of their own wealth were shaped by his association with Jamnalal Bajaj, and as such, it is of value to examine Gandhi’s theories of wealth and trusteeship in the context of Bajaj’s life and the factors that shaped it. In part one of this series, I examine the unique circumstances of Jamnalal Bajaj’s life that made him so fit for the role Gandhi had in mind.

Jaipur and Wardha

Bajaj was born in November 1889 to a poor family, in Kashi-ka-Bas, a waterless village near the city of Jaipur. When Jamnalal was about five years old, a rich trader, Bachhraj Bajaj, who had settled in Wardha in Maharashtra, returned to the village of his ancestors for a brief visit. His adopted son had just died, and he was looking for a boy among his distant relatives for his widowed and childless daughter-in-law to adopt. A young Jamnalal caught his wife’s eye. What followed was somewhat tragic. US Mohan Rao tells the story of a polite commonplace uttered by Jamnalal’s mother being pounced on by the wealthier family as a binding promise to give them the boy. And when his mother denied this, the matter was taken before the local caste panchayat, that ruled in favour of the Bajajs, who then adopted him. And while Rao glorifies Jamnalal’s birth family as being principled enough to give up the boy based on a chance utterance, it is quite likely that Bachhraj Bajaj’s offer to sink a well in the arid village did influence the decision of the panchayat.

The young Jamnalal was given the minimum schooling customary for boys of his caste and then trained in the Bajaj family business. And while he showed aptitude for the business, his adoption didn’t sit easily with him. At the age of 17, after a row with his adoptive grandfather, Bachhraj Bajaj, he left his house leaving a letter for the old man telling him that he renounced all claim to his wealth. Unlike a run-of-the-mill teenage tantrum however he was surprisingly thorough in his documentation. He even took the trouble to draw up a separate deed wherein he formally relinquished all claims to his grandfather’s money and waived his right to make such any such claim in a court of law. Bachhraj Bajaj, who seems to have been short-tempered but fond of the boy, is said to have hurried to the railway station and brought the upset teenager home. And while Jamnalal agreed to return home, he retained a vague sense of discomfort with what he saw as wealth to which he had no right.

When Bachhraj Bajaj died a little over a year later, and left him the sole heir to his wealth, this discomfort grew, and Jamnalal began searching for ways in which he could reconcile the growing gap between the life he led and the life he sought.

Enter, Gandhi

In his own words, Bajaj describes much of his youth as being spent searching for a method through which he could settle this vague discomfort with his otherwise prosperous, privileged life. He writes:

Even from an early age, I had a vague feeling in me that my life should be simple, purposeful, progressive and of service to others. Even when I was engaged in my various activities, I continued my search for such a guide. In the course of this search, I found Gandhiji, and that forever.

Enthusiastic in his quest (and of course, very rich), the young man managed to meet Rabindranath Tagore, JC Bose, Lokmanya Tilak and many others, and also remained in touch with them. But none inspired him with the affection that Gandhi would. He read about Gandhi and his work in South Africa and was instinctively drawn to him. When Gandhi returned to India in 1915, the 26-year-old Bajaj sought him out. Within a period of three years, the acquaintance had deepened to the extent that Bajaj begged Gandhi to consider him an adopted son. While he was impressed by both Gandhi and Kasturba Gandhi’s commitment to their chosen way of life, the deeper draw to someone like Bajaj, struggling with the question of his wealth, was Gandhi’s conceptual framework. On the impact of meeting Gandhi, Bajaj writes:

Mahatmaji completely revolutionised the very foundation of my thinking. Many a time I used to think of renunciation. He showed me the way to direct my thoughts to fruitful channels.

At the heart of this relationship lay both Bajaj’s genuine need for a father figure he could truly look up to, and Gandhi’s still developing doctrine of the trusteeship of wealth.

Trusteeship

Gandhi (perhaps owing to his own background) was instinctively comfortable with wealth and with the idea of the private ownership of wealth. He saw wealth like any other product, and the ability to make it like any other talent. He argued that if a man was good at making money, then he shouldn’t be restrained or discouraged from making it, as long as he understood that he held the wealth he created in trust for the rest of humanity. In an interview in 1931, he says:

I should allow a man of intelligence to gain more and I should not hinder him from making use of his abilities. But the surplus of his gains ought to return to the people… They are only the trustees of their gains, and nothing else. I may be sadly disappointed in this, but that is the ideal which I uphold.

When he was pushed further on how he would react to a proletariat revolution seeking a redistribution of wealth in independent India, his response is quintessentially Gandhi:

My attitudes would be to convert the better of classes into trustees of what they already possessed. That is, they would keep the money, but would have to work for the benefit of the people who procured them their wealth.

Critics of Gandhi often point out that this was an understanding which made life much simpler for his many capitalist friends, coinciding as it did with the rise of the USSR. His capitalist friends all contributed regularly to his various causes (for as Sarojini Naidu once remarked tongue in cheek, “it takes a great deal of money to keep Gandhi in poverty”), and seemed to interpret these donations as the sum total of their responsibility towards redistribution. Gandhi himself acknowledges this limitation, but argues that the failure of most capitalists to adopt this idea in full spoke of the weakness of the class itself and not of any weakness in the idea.

The donor, the worker

For Jamnalal Bajaj though, placing a vast majority of his resources at Gandhi’s disposal and adopting a simpler lifestyle was not a hardship. Both Bajaj and his wife, Janakidevi, who had been raised in purdah (a common practice in conservative upper caste Hindu families at the time), enthusiastically embraced the lifestyle prescribed by Gandhi, and Bajaj, despite his protestations of lacking a formal education was himself convinced to play a more leading role in the non-cooperation movement and the Congress, especially after Gandhi’s imprisonment for sedition. Bajaj led and was himself arrested in connection with the Nagpur flag satyagraha in 1923, a months-long civil disobedience movement where dissenters launched nationalist flags in direct disobedience of the law.

Bajaj’s financial contributions to Gandhi’s various causes were extraordinary in their scale. Kaka Kalelkar estimated Bajaj’s recorded donations to have exceeded Rs. 25 lakh over the course of his life. His unrecorded charity work quite possibly exceeded that. And unlike many modern day capitalist philanthropists, Bajaj is interesting in that he gave away his wealth as it accumulated, and not as a grand gesture after reaching a certain amount. As early as in the non-cooperation movement, for example, the 29 year old Bajaj donated Rs. 2 lakh (a huge sum at the time) for the maintenance of lawyers who had boycotted the courts in response to Gandhi’s call. At the end of his life, he left behind personal wealth of Rs. 5 lakh, which while substantial, was far less than what he donated over the course of this life. (This wealth was, in accordance with his wishes, donated to charity after his death).

But perhaps his more valuable contribution was in the deployment of his talents to give actual shape and form to many of Gandhi’s ideas. Devoted to the so-called constructive model of Swaraj, he served as treasurer to a vast number of Gandhi’s projects, including the Gandhi Seva Sangh and several spinners associations, which he ran with impressive efficiency. He also served as treasurer for massive fundraisers like the Tilak Swaraj Fund (which raised over Rs. 1 crore), and for projects perhaps closer to Gandhi’s heart like the financially precarious Jamia Millia Islamia college. Unlike Gandhi, who was often careless about the unintended consequences of his words, Bajaj was also acutely conscious of the meanings that could be ascribed to words and the unintentional harm that could flow from that, a talent that made him a useful part of the drafting at any Congress session. For example, he pointed out to Gandhi that the word “gau-raksha” (cow-protection) was inherently antagonistic to people who did eat beef, as it contained the presumption that there was someone from whom the cow had to be protected. He suggested the milder “gau-seva” or cow-service to embody Gandhi’s ideas on the cow, which Gandhi adopted. In a country where, to date, Muslims and Dalits are still lynched on the suspicion of cattle slaughter by self proclaimed “gau-rakshaks”, this has proven to have been extraordinarily insightful.

Examining the frequency with which he was deployed both personally and professionally by Gandhi — he did everything, from taking care of an appendicitis operation for Devdas Gandhi, to visiting the north-west frontier province to broker a peace deal when violence broke out between the Pathans and a small Hindu community that lived there, to personally examining the troubles of khadi associations in Bihar — it is impressive that he still managed to devote enough time to expanding his grandfather’s business and continue to make money to donate to Gandhi’s causes. In 1926, two years after his release from prison, he was to found Bajaj Industries, a conglomerate that survives today, and which was to thrive despite the repeated arrests of Bajaj himself, Janakidevi and his son, Kamalnayan.

Conclusion

While Bajaj often credited Gandhi with providing him a framework within which he could deploy his talents in a manner more meaningful than renunciation, it is also clear that Gandhi, both consciously and unconsciously, took Bajaj as a sort of model for what was possible within his trusteeship framework — after all, in 1931, when he gave the interview mentioned, he had for over a decade considered and treated Bajaj like an adopted son.

Analysis of Gandhi’s trusteeship framework often ignores the fact that Bajaj, for complicated reasons, came to Gandhi fully ready to renounce his wealth. While this level of detachment from wealth became unconsciously presumed in Gandhi’s idea of trusteeship, it was not an idea or starting position shared by many other capitalists. As a result, Gandhi’s ideas on the matter remained very much in the realm of the whimsical instead of the possible.

(In Part 2 of this series we examine the limitations of Bajaj’s own efforts in the context of the problems with the Vidya Mandir scheme and the limitations inherent in public policy driven by wealthy donors.)

Excellent piece! Waiting for the next one!