The Violence that Binds

To make sense of #IndiaAgainstPropaganda, we have to step away from the farmer protests and discuss some of the factors driving discourse in “New India”.

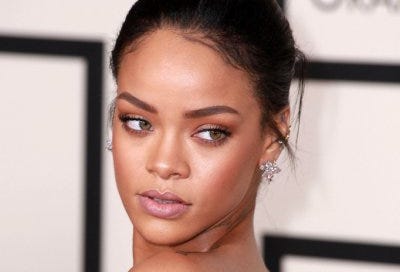

It’s been a decidedly strange couple of days for most Indian political watchers. Late on Monday night, global R&B sensation Rihanna tweeted “Why aren’t we talking about this?” with a link to a CNN story about the Indian farmer protests and unleashed an online explosion. Shortly after, global climate change activist Greta Thunberg added her support. As several pro-government Twitter handles moved desperately to contain the fall-out of those six words to Rihanna’s 100 million global Twitter followers, a bunch of scattered messages began to emerge. While the initial response was a largely incoherent mix of the tweet being “paid-for”, some general patriarchal abuse at Rihanna herself, including a extremely distressing glorification of her former partner Chris Brown (who was convicted of intimate partner violence against her) and Kangana Ranaut returning to her original “these are terrorists not protestors” rhetoric, by the morning, a clear message had emerged: The tweet was apparently the result of the efforts of “vested interest groups" that are trying to mobilise international support against India. Incredibly, the statement was delivered not by one of the many stars known to support the present Indian government, but directly by the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, together with two hashtags — #IndiaTogether and #IndiaAgainstPropaganda.

While Indian celebrities busied themselves for the rest of the day tweeting (at times identical) regurgitations of the same ministry approved message, media outlets busied themselves with building an even crazier theory. The online toolkit shared by Thunberg (fairly standard practice in online activism) was proclaimed across the networks as “proof” of a conspiracy, and by the next evening, the Delhi police announced that it had launched an investigation into the unnamed creators of the toolkit. All of this has been accompanied by online trolling, abuse and death threats not just against the celebrities who tweeted in support of the farmers, but also against foreign women journalists covering the story.

And while foreign affairs experts remain bewildered by what on the face of it looks like an epic overreaction to a couple of tweets, to people watching Indian politics closely, none of this is entirely unexpected. To understand what is happening today, we have to step away from the farmer protests and discuss some of the factors driving the larger “New India” narrative.

Authoritarianism Beyond Hindutva

While Hindutva has certainly been the predominant rallying cry for the BJP and its voters, the farmer protests and the state’s reactions to it are driving home an important realisation: The model of borderline authoritarianism preferred by the BJP and its supporters is not just a means to attaining a Hindu Rashtra — it is a separate end in itself. Simply put, it involves the establishment and maintenance of a favourable social order through violence. While this violence can be, and often is, administered by local goons, the more refined supporters of the government would prefer the violence to be judicial or at least quasi-legal. The denial of bail to activists jailed in the Bhima Koregaon case, many of whom have now been held without trial for close to three years, the arrests of Muslim men in relationships with Hindu women under questionable anti-conversion laws, or the denial of bail by the Madhya Pradesh High Court to comedian Munawar Faruqui on the charge of offending religious sentiments (the Supreme Court has since granted Faruqui bail) are all cheered by supporters of the government.

And while Hindutva has certainly been the main driving force in deciding what this social order will be, the farmer protests are demonstrating that this is not set in stone. Many of the protesting farmers themselves voted for the BJP and its polarising politics. The UP farmer leader Rakesh Tikait, for example, is accused of inciting violence during the Muzaffarnagar riots that killed dozens and displaced tens of thousands of Muslims. And yet, they now find themselves on the wrong end of the currently preferred social order — a neoliberal one, with large corporate interests driving economic policy.

Narendra Modi’s urban voter base has proven to be receptive to trading their old prejudices for new ones. In this new discourse, there is no more “Jai Jawan Jai Kisan”. To them, the protesting farmers are a burden on honest taxpayers. They are “rich”, “over-subsidised” and “greedy” and must not be allowed to dictate terms to a democratically elected government. And after the actions of January 26, they are all to be branded traitors or “khalistanis”. This is part of a larger shift into authoritarianism beyond the Hindutva fold. On February 1, BJP cadres attacked the house of Dharma Reddy, a TRS MLA in Warangal, for alleging irregularities in the funds being collected by organisations affiliated with the BJP for the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. It’s worth noting that Reddy is himself both Hindu and pro Ram Mandir. His questions related merely to the scale of funds being collected by the BJP in Warangal.

Now none of this should be taken to minimise or trivialise the threat faced by Muslims and other minorities from Hindutva — that remains unchanged and very serious. It is just important to highlight that the commitment to the authoritarian state project extends beyond Hindutva.

The people’s strongman

Since January 26, pro-Modi social media has been filled with calls for the state to use extreme force against the protestors, and groups of violent demonstrators claiming to be locals (some of whom have now been shown to have BJP links) even managed to enter the protest site at Singhu border and engage in violence despite the huge police presence. The message from Modi voters is fairly simple. The farmers must be shown their place, immediately, and by force if necessary.

And here lies the crux of Mr. Modi’s dilemma. He came into power with a huge strongman image (“56 inch chest”), and this strongman was to deliver growth that would take the country to global superpower status (“Vishwaguru”). This would be a new, confident India that wouldn’t back down from challenges (as the Minister of External Affairs himself was at great pains to tell, presumably, Rihanna). Large scale, knee-jerk and ill-thought out economic policies like demonetisation were all hailed as “masterstrokes” purely for their “decisive” nature. It didn’t matter that they were decisively bad for the economy. But while his voters have been willing to deny, overlook or make excuses for his policy failures, they expect the strongman image to be maintained at all costs. This gives the government very little wriggle room in their negotiations with the farmers.

Now Mr. Modi’s voter base does not seem to be particularly interested in the specifics or the scale of violence that would be required to forcefully evict an estimated 500,000 protestors together with their tractors and trolleys. The answer the Indian government has gone with has been increasingly draconian restrictions: Concrete barricades, medieval looking spikes in the road and cutting the protestors internet, electricity, water and access to toilets. Concertina wire now blocks some of the main entrances into the national capital, journalists are turned away from the protest sites, and young farmers who have arrived to swell the ranks at almost all the protest sites now undertake guard duty at night to prevent a repeat of the violence at Singhu.

None of this has gone down well internationally. The image of concertina wire and nails in the road hardly give the impression of a thriving democracy. The arrest and detention of Mandeep Punia, an independent journalist who exposed the links between the “locals” who stormed the protest site at Singhu and the BJP, and the arrest of Nodeep Kaur, a young labour rights activist have sharpened the perception that all is certainly not well in the world’s largest democracy.

And the Indian government’s age old cry of “this our internal matter” hasn’t quite worked in the manner anticipated.

The diaspora wildcard

Few people understand the power of India’s 20 million strong diaspora community better than Mr. Modi. The Hindu diaspora in particular has been given pride of place by this government, and has responded enthusiastically. Indian-American writers like Sadanand Dhume have been at the forefront of the effort to minimise and whitewash the more troubling aspects of Mr. Modi’s politics. But the problem with a foreign policy centered around the Indian diaspora is that it is not a door that one can close at will.

The Sikh diaspora in particular, with their strong roots in agrarian families in Punjab have extended solidarity to these protests and have kept international attention on the farmers. And as more and more global celebrities add their voices to the voice of the diaspora, each of the government’s strong arming repressive moves (mostly undertaken to please their own voter base) only contribute to the global conviction that all is not well. And while old hands like Mr. Dhume continue to trumpet both the benefits of the laws and minimise the human rights violations happening on the ground, it is unquestionably a difficult sell. The global solidarities built by the Black Lives Matter movement have now come to the party, and the abuse, trolling and threats of legal action that they have faced are unlikely to do anything other than strengthen their voices.

Conclusion

While it is easy to attribute the length of the stand-off to things like “ego”, a word used by both sides to blame the other, the current crisis must be seen in a larger context. Over the last 8 years, Mr. Modi has steadily spun national pride into his own political identity. As a corollary to this, the language and narrative of “New India” has seeped in to every day social, political and cultural affairs, to the extent that it is often difficult to distinguish the words of our cricket team captain from the words of the External Affairs Minister. Both speak of a new India, self confidence and “pushing back”. And as several attempts to “push back” against the farmer protestors have not delivered the anticipated results, the government seems to be engaging in the next best thing: a full scale online combat with, well, a global cabal led by Rihanna and Greta Thunberg.

Now this strong, unrelenting “new India” is a narrative in which many are deeply invested: supporters of Hindutva, supporters of Mr. Modi’s promises of neo-liberal reform and the Hindu diaspora. In this framework, there is very little room for admissions of error, willingness to go back to the drawing board, or to heal fractured relationships. And unfortunately all of these are essential to resolve this crisis.

Everything was happening so fast, I couldn't get hold on all of them. Thanks. This article made sense.