Jamnalal Bajaj and the limitations of philanthropic capitalism

Part two of a two part series on Jamnalal Bajaj, Gandhi and the possibilities and limitations of philanthropic capitalism.

Of Mahatma Gandhi’s many capitalist friends, Jamnalal Bajaj is perhaps the easiest to acquit of any desire to use Gandhi’s trusteeship framework for his own benefit. It is fair to say that he was entirely committed to using a large proportion of his wealth for the good of the community. It is still however useful to examine what interventions he considered to be good for the community, and how those interventions played out over the course of his life.

Critics of Gandhi often point to his fairly undemocratic decision making process. Steeped in a philosophy entirely based on individual responsibility, Gandhi, when he became convinced of the merit of his own actions, rarely listened to criticism or alternative points of view, and could pull out all stops (short of physical violence) to carry his point through (Perhaps his fast around the 1931 Poona Pact on separate electorates are the best example of this — he gave little thought to the repercussions and violence that the Dalit community would face if his fast were to end with his death.). This inability to adequately listen to stakeholders was to turn some of Bajaj’s chosen philanthropic endeavours into flashpoints, especially when these endeavours reached the realm of public policy.

In part two of this series, I examine Bajaj’s life and the influences that led him to choose the philanthropic interventions that he did, and the impact of some of those interventions on politics in India.

The businessman Swarajist

In a foreword to Kaka Kalelkar’s 1951 book on Jamnalal Bajaj, Jawaharlal Nehru best describes the unique role Bajaj played in the broader independence movement. He writes:

I think it would be true to say that Jamnalalji brought to it a special and rare quality. Most of us were like others and could perhaps be spared, for others could take their place. But Jamnalalji was rather unique in his own way, for many of his kind did not come into the movement, with that devotion that he brought to it… It was a great blow to all of us when he left us in the prime of life. There was no one to take his place.

In the Congress, which at the time was very much a party of academics, thinkers and lawyers, Bajaj stood out. He laughingly described himself as “ignorant”, but this was hardly true. While he had been given a mere four years of formal schooling, he had been taken into his grandfather’s business to learn on the job. Under his grandfather, Bajaj was drilled in bookkeeping, reading commercial contracts, and evaluating commercial proposals, and could, at the age of 18 on the death of his grandfather, run the business without difficulty. These skills were immensely valuable to Gandhi, whose constructive ideas of Swaraj needed people who could effectively fundraise, manage large sums of money and run large-scale decentralised projects, far more than it needed public intellectuals.

Many of Gandhi’s businessman friends donated large sums of money to the movement and also hosted Gandhi frequently, but few were willing to devote as much time as Bajaj did to the day to day workings of the various projects of constructive Swaraj. 30 years after Bajaj’s death, his wife Janakidevi described the amount of work Bajaj did for Gandhi rather poetically. She said:

“Gandhi was a storm that blew my husband hither and tither”.

By 1925, this description was certainly apt. The 34-year-old Bajaj was serving as the treasurer of the All India Deshbandhu Memorial Fund, the All India Spinners Association and the Tilak Swaraj Fund, in addition to a host of other smaller funds in relation to the propagation of Hindi and the eradication of untouchability. He had founded the Gandhi Seva Sangh in 1923 and the Mahila Seva Mandal in 1924. Committed to Gandhi’s ideas on “national” universities, he was closely involved in the formation of the Gujarat Vidyapeet, and was also in charge of the funds being raised for Hakim Saheb Ajmal Khan’s proposed national university in Aligarh (this was later moved to Delhi as Jamia Millia Islamia). Kalelkar points out that Bajaj took his role as treasurer of each of these funds extremely seriously — actively collecting funds, making sure funds were properly utilised for the purpose for which they were collected and maintaining strict accounts. Bajaj toured the country extensively bringing in support for Khadi, the propagation of a rashtrabhasha, the abolition of purdah within the Marwari community and to bring more businessmen into the national movement. He also travelled with Gandhi on his many trips, often acting as both son and advisor. Bajaj was imprisoned in connection with his work three times — in 1923 for the Nagpur flag satyagraha, in 1932 in connection with the salt satyagraha and in 1939 in the princely state of Jaipur. In 1933, he was elected treasurer of the Congress, a post he held for a few years.

All of this was in addition to Bajaj’s “day-job” — growing and diversifying the mainly moneylending and cotton trade business his grandfather left him. Inheriting a business estimated to be worth around Rs. 5 lakh in 1907, Bajaj had, by 1920, donated close to this amount to various causes including the national movement. Bajaj was also a part of the evolving Bombay industrialist community. Stalwarts like Dorabji Tata took an interest in him, and even offered him stock at a discounted rate to get him to invest in selected industries (an offer Bajaj is said to have refused). In 1919, Bajaj was part of the conglomerate of Indian businessmen, Sir Victor Sassoon, Sir Lallubhai Samaldas, Ramnarain Ruia and the Tatas who founded the New India Assurance Company — India’s first general insurance company, where he served as a founder director. While Bajaj later resigned citing his principled differences with the rest of the board on how a truly “swadeshi” company should be run, his relationship with them remained cordial.

By the 1920s, Bajaj’s business was expanding at a rate that was rapidly outgrowing the partnership structure. When his grandfather’s erstwhile partners objected to his firm’s charitable donations, he bought some of them out of the partnership and founded the Bajaj group of industries in 1926. In 1931, he incorporated Hindusthan Sugar Mills Ltd as a limited company under the 1913 Companies Act, ushering in the era of a conglomerate that survives today.

Philanthropic philosophy - education and Hindi

While Bajaj’s methods of doing business and his views on wealth were influenced by Gandhian ideas of business ethics and trusteeship, the areas in which he chose to work were often driven by the gaps he perceived in his own life — specifically, education, and the substitution of English with a rashtrabhasha. Even before he met Gandhi, education was an important part of his philanthropic activity. Deeply impressed with the work of Jagdish Chandra Bose, he donated Rs 31,000 to set up a research institute in Calcutta. He also donated Rs. 50,000 towards a library at the Benaras Hindu University.

After meeting Gandhi, Bajaj’s ideas on education began to take more concrete shape. In Wardha, he began a girls school for the children of people involved in the independence movement. In 1923, Vinayak Narahari (“Vinoba”) Bhave came to live at the newly opened Satyagraha Ashram in Wardha. Bhave, whom Bajaj immediately took to, was deeply influenced by Gandhi’s developing ideas on education — schooling that involved rejecting English as the medium of eduction, learning basic skills like spinning in addition to basic learning, and schools being self supporting enterprises. This was the bedrock of what later become known as the Wardha Scheme of Education.

Bajaj himself never spoke English fluently or comfortably (though he did read and write in it). In 1920, when he was offered the Chairmanship of the Reception Committee of the Nagpur Congress session, he wrote to Gandhi expressing his doubts about his suitability for the role, citing his inexperience, and lack of qualifications. Mahadev Desai wrote back on behalf of Gandhi forcing him to accept it, and pointing out that his speech could just as easily be made in Hindi and translated into English.

In 1937, speaking at the All India Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, Bajaj speaks of the origins of his interest in propagating a common national language.

When I was present at the historic Calcutta Congress session held in 1906 under Dadabhai Naoroji’s presidentship, and the entire proceedings were conducted through the medium of the English language, I was able to understand very little of it. At that time I felt that it was a matter of sorrow and anxiety that being Indians in our own country, we have to conduct our affairs in a foreign language.

The schemes funded by Bajaj for primary education and for the propagation of Hindi were all moderately successful. But when it came to translating these ideas into educational policy, the Congress soon ran into serious difficulties.

Provincial governments and the Vidya Mandir Scheme

The Government of India Act, 1935, separated Burma from India and provided for the creation of provincial governments in the 11 provinces left in India, with significant autonomy. Bajaj was strongly opposed to the Congress contesting in these elections, given how they fell significantly short of the demand for complete independence, but was overruled by Congress stalwarts like Gandhi and Sardar Patel. While the Congress did well in the 1937 provincial elections (mostly due to its longstanding stature as an organised national party), their governance failed to win the confidence of the local Muslim communities they served. Mushirul Hassan, explaining the meteoric resurgence of the Muslim League between 1937 and 1940 points to several grievances (both real and imagined) that reinforced fears of Congress rule being Hindu rule by another name — and the grievances, at least in the Central Provinces and Berar, related disproportionately to education.

In 1937, Gandhi convened an All India Educational Conference at Wardha, where he was now based. A group of academics, led by Dr. Zakir Hussain (who was then also the Vice Chancellor of Jamia Millia Islamia) were chosen to prepare a primary school syllabus that would capture most of Gandhi’s ideas on primary education, including teaching in the mother tongue, and skill development — the Wardha Scheme.

In 1938, pursuant to a Congress resolution, a form of this Wardha Scheme was adopted in the Central Provinces, by Pandit Ravi Shankar Shukla, which was termed the Vidya Mandir Scheme. At the outset, the name “Vidya Mandir” itself, translating loosely into “temple of knowledge”, fed into an atmosphere of growing distrust among the Muslim community. Dr Zakir Hussain, warning of this, remarked:

there is a strong feeling against the use of the name among a section of the people in as well as outside the province. I have taken pains to assure myself that the feeling is genuine and sincere.

The second flashpoint was on the question of what this “mother tongue” would be. In the Central Provinces, this was defined as the language of the area (Marathi) and Hindi, while Urdu was excluded. This was part of a broader issue — with the language of governance moving to Hindi, a large number of Muslims, who had been educated and were proficient in the Urdu script were being excluded from government jobs and opportunities. Shukla, himself a strong supporter of Hindi as the national language, was busy introducing it into all levels of government. The exclusion of Urdu from the syllabus was felt deeply by the Muslim community.

The third flashpoint was the compulsory chanting of Vande Mataram by students, which is still often invoked by communal forces in India to target the Muslim community.

The Jamiat-i-Ulama-i-Hind, who were supporters of the Congress, constituted a sub-committee to evaluate the Wardha Scheme. Joachim Oesterheld points out that the committee took issue with the aim of the scheme, “to produce a class of educated people having the same kind of culture, faith and practices” as neither practical nor desirable in a pluralistic country. The committee made several recommendations, but Shukla was not inclined to take them seriously. At any event, the damage was done — despite the small scale roll out of the Vidya Mandir scheme, it, and the Wardha Scheme in general, were both seen as an attempt to establish the dominance of Hinduism using primary education, and became a rallying cry for the Muslim League. Some of this feedback reached Gandhi, but as it came mixed with other grievances at a time of increasing polarisation, much of it was perhaps unfairly dismissed by him. In particular, his assertion that he had no control of how the local Congress Ministers interpreted his schemes, and his insistence that the mother-tongue could only be the language spoken in the area, only served to distance him and the system of education further from the Muslim community.

Complexities

Bajaj’s life was unquestionably extraordinary, but he was also a complicated individual, given to extreme episodes of self blame for his imagined failures to live up to wholly unrealistic standards. Writing to Gandhi on his 49th birthday, Bajaj writes about his constant struggles:

While thinking about my weaknesses during these years, and especially after the tragic death of Chhotelalji, my mind often turned to the idea of suicide. I have tried to shake it off, because I considered suicide as cowardice and sin, and my intellectual conviction still remains the same. What pains me more is the fact that I am going downward instead of rising in the spiritual scale… Today, however, I am afraid that if the present state of mind continues, I shall either reach a stage of insanity or shall be dragged down the path of degradation… Death, I cannot invite at will. Suicide I hold to be cowardly and sinful. I am therefore at a loss to know what to do.

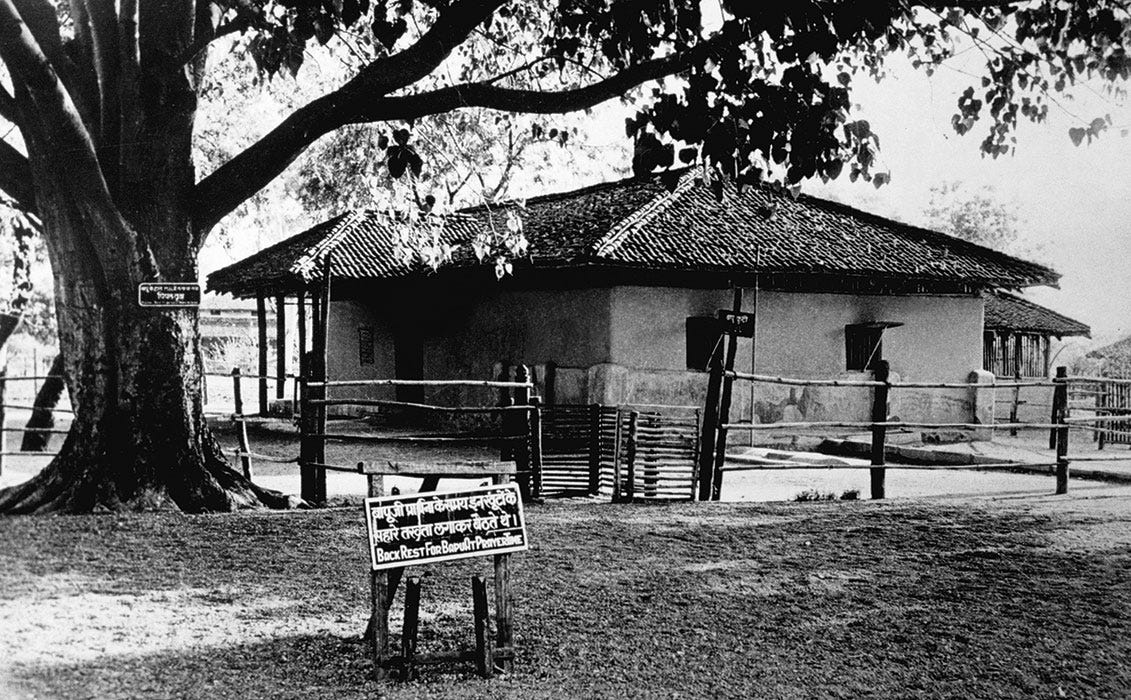

And while he continued his work during this time, including an independent agitation in the princely state of Jaipur, which led to his own imprisonment there for many months, he found himself increasingly disturbed. In the final years of his life, with Gandhi’s permission, he retired to a small mud hut that he built in Wardha, and spent all his time attending to cows that he had rescued from slaughter. He died there in 1942, at the age of 53.

Conclusion

There is little doubt that Bajaj’s philanthropic efforts were deeply impactful, both in terms of the amounts he donated and the causes he chose to highlight. As discussed in the first article in this series, moves like temple entry, opening of wells and employing a Dalit cook were extraordinarily powerful at the time and came at some personal cost for him and his family, including threats of excommunication and stones being pelted at Bajaj himself. Led by his wife Janakidevi, and his daughters, the movement against both child marriage and purdah within the marwari community were also influential. And in his lifetime, his efforts to propagate Khadi and his interventions in the princely state of Jaipur were also successful. But perhaps Bajaj’s most lasting contribution was in the unique organisational abilities he brought to the independence movement in general. It is unlikely that many of Gandhi’s endeavours would have reached the scale they did without Bajaj to implement them.

Bajaj by all accounts was a man of character, and his commitment to Hindu Muslim unity was both consistent and praiseworthy — he was himself seriously injured in 1924 trying to stop a communal riot in Nagpur. Unfortunately, Gandhi and Bajaj’s favoured form of education when enforced top down by a government had serious consequences on communal harmony that they did not anticipate. It was, in hindsight, a classic example of a situation where practical consultation with the stakeholders (parents of children of all communities who were to study in these schools) would have served far better than the lofty ideals of Gandhi and Bajaj.

The unintended communalisation of the Wardha Scheme of Education is a useful reminder to the governments of today — while private philanthropists can always do what they choose with their money, governments must never be so blinded by these ideas that that they cease to listen to the actual stakeholders of their policies.

(Part 1 of this series examined the unique circumstances of Jamnalal Bajaj’s life that made him the role model for Gandhi’s ideas on the trusteeship of wealth.)

Note: The propagation of Hindi, for both Gandhi and Bajaj meant the propagation of Hindustani - a mix of Hindi and Urdu that they believed would be understandable by both Hindus and Muslims. This was not necessarily a vision shared by the rest of the Congress.

Very interesting!